Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Psychology | | Children of Narcissus | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

5. Media Portrayals

Copyright © 2008, Paul Lutus — Message Page

(double-click any word to see its definition)

Here are some examples of narcissism as portrayed in the movies.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

In my opinion, the strength of this cinematic story, remade four times to date, comes from its connection with narcissism. Reviewers of the first version (1956, starring Kevin McCarthy) saw it as an allegory for the McCarthy/HUAC Communist witch hunt that preoccupied the country at the time. Well, I agree — but I think the McCarthy era was itself an example of high-level narcissism. Joseph McCarthy, the key figure in that sad chapter in U.S. history, was very clearly a malignant narcissist with the attachment to authority this article analyzes. In period newsreel footage of Tail-gunner Joe McCarthy, you can see the driven, sanctimonious, dogmatic behaviors that are hallmarks of narcissism with an authority attachment.

"Invasion" has some original plot elements in a genre known for shameless copying of things that have worked before. Of course, now that the film has been remade four times it's become its own cliché. But in 1956 it was original and pretty spooky. It's a story about a secret alien invasion in which the aliens intend to take us over one body at a time, rather than by a big confrontation as in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, starring Michael Rennie), an excellent movie with an anti-war theme at the beginning of the cold war.

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that the sneaky aliens want to put a big seed pod near where you are sleeping, and when you wake up, you've been sort of cloned by the seed pod and your original body is an empty shell. You're basically the same person with the same memories, but you've been transformed into a booster for the alien cause — as well as emotionless, driven, focused on the goal of converting everyone around you, and without a trace of doubt about The Plan. After being taken over by a seed pod, a typical character might say something like, "What's wrong with you? Why aren't you like us?" Yes, you guessed it — a stereotypical portrayal of clinical narcissism.

Like most memorable films, some elements of Invasion have made their way into everyday speech and thinking. I can't tell you how many times I've heard someone use the expression "pod people" to describe someone with too little emotion or humility or too much attachment to a dogmatic idea, which happen to be traits of clinical narcissism.

The original screenplay for the 1956 Invasion had a rather dark ending, with the Kevin McCarthy character screaming at passing trucks filled with seed pods, but the producers wanted — and got — a more upbeat ending in which an alarm is raised just in time to save the world. I personally prefer the darker ending in the 1978 remake starring Donald Sutherland. In the last scene of this version, Veronica Cartwright's character slips up to Donald Sutherland and whispers to him about her recent experiences evading the sneaky aliens. The supposedly trustworthy Donald Sutherland character suddenly points at her and emits an unmistakably alien scream of alarm (see picture this page). Much better.

By the way, Kevin McCarthy has a cameo appearance in the 1978 remake, as a crazed pedestrian who bumps into the car of the principal characters and starts the story rolling. In the same way, Veronica Cartwright gets a cameo in the 2007 remake. Here are the four versions of Invasion:

Year Starring Comments 1956 Kevin McCarthy, Dana Wynter, King Donovan, Carolyn Jones Made in an era when films were obliged to tell a story — unlike now, you couldn't just blow stuff up for two hours. 1978 Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams, Jeff Goldblum, Veronica Cartwright, Leonard Nimoy Better ending, more complex story. Brooke Adams' awakening scene by itself redeems the viewers' patience. Kevin McCarthy (from the 1956 version) has a cameo appearance. 1993 Gabrielle Anwar, Terry Kinney, Billy Wirth This version has some interesting twists, but it doesn't stray too far from the genre. 2007 Nicole Kidman, Daniel Craig, Jeremy Northam I haven't seen this version yet, it seems to be well received. Veronica Cartwright (from the 1978 version) has a cameo appearance.

Fatal Attraction

To me, Fatal Attraction (1987, Michael Douglas, Glenn Close, Ann Archer) is a perfect portrayal of clinical narcissism. The Michael Douglas character has what he expects will be a one-night stand, but it turns into a nightmare of relentless stalking when Glenn Close's character won't face reality. In a key scene, the Glenn Close character says "Well, what am I supposed to do? You won't answer my calls, you change your number, I'm not going to be ignored, Dan!" This is a classic of clinical narcissism, because when confronted by a narcissist you have only a few options — you can escape, or you can become an acolyte, but you cannot ignore them. They are secular Jehovah's Witnesses and you might as well stop struggling, because you will be assimilated (and see Borg below).

Fatal Attraction became a big hit both domestically and abroad, receiving six Academy Award nominations including Best Picture. The film popularized the term "bunny boiler," to describe a relentless stalker, usually a woman, for a scene in the movie in which the Glenn Close character slips into her target's house and boils the family pet on the stove.

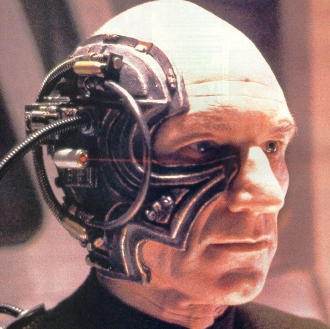

The Borg / Star Trek

Not a feature film per se, but a plot element in the Star Trek franchise, the Borg are sort of a hive mind, a collective consciousness intent on dominating the weak, emotional humans. As commonly portrayed, the Borg are emotionless cybernetic drones intent on converting you to their cause — which makes them seem derived from the pod people from "Body Snatchers" as well as several other sources. The Borg are presented mostly as stiff and unresponsive and have just a few thoughts to share, among which are "resistance is futile" and "you will be assimilated."

When I see a Borg portrayal in Star Trek I can't help thinking of Joe McCarthy's nasal, monotone delivery during the Army-McCarthy hearings. If Tail-gunner Joe only realized how he sounded. This, by the way, is a classic of narcissism — they have no idea how they look to others.

The Borg characters, like other narcissism portrayals in media, successfully convey their essence without being too explicit. When we see a member of the Borg collective, or a "pod person" from Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or a character like Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, no explanation is necessary — we instinctively realize they don't care who we are as individuals, only how we can be made to serve their immediate goals. They very clearly intend to see how quickly they can exploit us, and they really don't care who we are. Put simply, these are narcissistic portrayals.

Conclusion

My intent in this section has been to explain that narcissism isn't strictly speaking a psychological term or specialty, although psychologists spend a lot of time describing it (as usual without explaining it). People recognized narcissism for what it was long before psychology existed, a fact exemplified by the condition's association with the Narcissus myth.

Narcissism represents a special problem for the field of psychology, because psychology as it is presently practiced is not a science, it is a system of beliefs loosely supported by something resembling research, but without the falsifiable theories that could forge a link with science. Consequently and ironically, psychology may serve as a haven for clinical narcissists in the same way that religion does and for the same reason — an association with temporal authority that carries a lot of weight, but one that cannot be effectively challenged using evidence.

Narcissists are attracted to a particular kind of authority — it must be persuasive and respected, but it must be malleable enough that the narcissist can twist it to his own purposes. Contemporary psychology meets that description, as does religion, politics, some kinds of police work, and various flexible definitions of the term "expert."

The only effective weapon against these misuses of authority is a strict adherence to scientific principles — primarily science's focus on evidence and falsifiability. In my debates with psychologists over the years I've seen endless repetitions of the same kinds of arguments — psychology is a science because people say it is, because a panel of experts declared it a science, because it is popularly thought to be a science, because if psychology were to be recognized as a non-science those in need of treatment would not know where to turn. The problem with these arguments is that none of them meaningfully address the original question. Ironically, because these silly arguments are put forth by psychologists supposedly trained in science, they serve to answer the original question in the negative.

If psychologists were actually trained in science, they would know how to debate scientific topics, and they would simply present the evidence — here are the clinical practices that have been halted because they are (not supported by / have been contradicted by) scientific evidence (none to date), here is the scientific evidence that Asperger's results from (blank), can be unambiguously diagnosed using (blank) and can be effectively treated with (blank), as a result of which psychology can now justify designing a clinical practice focused on Asperger's. But this is not how psychology works, this is not how psychologists are trained, and as a result I receive absurdly juvenile arguments in favor of psychology as a special kind of science that doesn't have to meet the standards of that other kind of science — you know, the real kind.

References

| Home | | Psychology | | Children of Narcissus | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |