Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Psychology | | Children of Narcissus | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

4. Authority

Copyright © 2008, Paul Lutus — Message Page

(double-click any word to see its definition)

Here are examples of psychological roles that associate narcissism and authority.

The Policeman

First, please excuse my not using the P.C. expression "Police officer." It's too cumbersome.

Not all narcissistic "policemen" are duly authorized officers of the law. Many are narcissists who focus an inordinate amount of attention on rules that, apart from them, no one cares about. Some invent rules of their own, then try to enforce them. This narcissistic role is complicated by the fact that many of its members are both narcissists and OCD sufferers.

In normal life, regardless of how many rules there are, most are not enforced unless their violation represents an injury or inconvenience to someone. In ordinary circumstances, unless there is a victim no one cares, and this pragmatic outlook extends (or should extend) to courts of law. In evaluating legal issues, justices are expected to ask themselves a series of practical questions, including, "where's the harm?" An example might be an unofficial nude beach — a group of people want to sunbathe in the nude, they've chosen an unused, secluded area, where's the harm? Obviously someone could make the argument that they are technically breaking a law against public indecency, but normally in a case like this, there's no enforcement unless a citizen files a complaint.

Enter the narcissistic policeman, whose motive is not public order or justice but control and domination. In our hypothetical nude beach example, it doesn't matter whether the "policeman" is a duly authorized officer of the law or a busybody narcissist — if he chooses and is inclined, the "policeman" can make a lot of trouble for the sunbathers, regardless of how careful they are not to irritate public sensibilities.

One can usually distinguish a narcissistic policeman from the ordinary kind. A narcissistic policeman will harass you based on the letter of the law, asking only "is it legal?", while a normal one will only bother you if your behavior violates someone's rights — before taking an action, the latter will always ask the justice's question, "where's the harm?"

"Is it legal?" is important in some contexts, but no one expects all laws to be enforced in all circumstances, except possibly a narcissist. "Where's the harm?" is a more pragmatic approach, and it is the standard most likely to be applied by a seasoned, non-pathological policeman. Therefore if you meet a policeman who seems to care more that a law has been broken than whether any harm is done, chances are you are in the company of a narcissist, whose agenda is control and domination. By the way — if you are confronted by a uniformed policeman, and if you believe he is a narcissist intent on harassing you for no perceptible reason, for God's sake don't share your conclusion with him. The danger is that you may be right — ever hear of "narcissistic rage"?

Philosopher Ayn Rand wrote that a government could achieve total domination by passing laws so numerous and contradictory that every citizen becomes a lawbreaker, allowed to walk around free only through the forbearance of the authorities. That is a perfect description of the narcissistic policeman role, as well as an approximate description of modern times.

"There's no way to rule innocent men. The only power any government has is the power to crack down on criminals. Well, when there aren't enough criminals one makes them. One declares so many things to be a crime that it becomes impossible for men to live without breaking laws."

— Ayn Rand, "Atlas Shrugged", 1957

The Preacher

Nothing compares to a narcissist who has attached himself to God — it's the quintessential shield against reality. A policeman might have to defend his actions in court from time to time, but one can't appeal to the Almighty in any practical sense. The narcissist/preacher role is essentially perfect, indeed it's hard to understand how anyone can become a preacher without also becoming a clinical narcissist as a side effect.

In case you wonder how the Church of the 17th century could burn Giordano Bruno at the stake, then threaten Galileo Galilei with torture, in order to defend beliefs that were quite obviously false, the answer is simple — narcissism. I mean the kind of simple-minded narcissism that chooses a handful of shallow beliefs suitable for a life spent on the brink of intellectual bankruptcy, then tries to kill anyone who believes anything else.

When you are in charge of a flock of intellectual sheep and someone points out that some of your beliefs are indefensible, you can't just acknowledge the error and say to the flock, "Oh, we were wrong about this divinely inspired law, all you sheep need to adjust your thinking" — this isn't how religion works. When confronted by the prospect of acknowledging error, a True Believer would prefer to fly an airliner into a building. As it happens, just like True Believers, clinical narcissists are constitutionally unable to acknowledge error and are prone to rage at the suggestion of any personal shortcoming. I'm sure it's just a coincidence.

With respect to the matters brought to the Church's attention by Bruno and Galileo, the Church did eventually apologize — in 1992, 359 years after Galileo's trial and house arrest. This kind of alacrity in the face of error cannot escape the attention of narcissists, whose congenital inability to acknowledge error would seem to find a natural home in religion.

Someday, when psychology is a science, a diagnosis of clinical narcissism won't be a matter of opinion as it is now. The diagnosis will be deterministic, based on something more substantial than a conversation with a psychologist. We'll be able to properly diagnose narcissism as we now diagnose the flu. That won't end religion, of course — that would be too unkind to the weak-minded. But religion will have a different name, and there might even be a treatment.

The Teacher

This example may seem unfair to teachers, often pictured as humble, self-sacrificing purveyors of truth, but remember I am focusing solely on teaching's utility to a narcissist, it isn't meant to disparage teaching as a profession. In the same way that not every policeman is a narcissist, and ... oh, let's not consider whether every preacher is a narcissist. For the clinical narcissist, there are certain irresistible varieties of mischief built into the relationship between teacher and student.

As with the other examples, distinguishing a narcissist from a normal teacher can be relatively easy (but not always, see below). A normal teacher will encourage and support any method for efficiently taking in new information. If a student wants to perform experiments, or explore a library, or form teams and create group assignments, all these have their place. But a narcissistic teacher requires a complete focus on his particular methods, which usually consists of boring, interminable lectures, followed by chapter assignments in a textbook he happens coincidentally to have written.

But a larger risk with narcissistic teachers is that they may begin to offer their own views and beliefs as though it is material germane to the topic being taught. The students are usually not a in a position to detect this switch, indeed they may not realize it for years. In the extreme version of this behavior, the teacher becomes a guru and proceeds to emotionally control the students, who at some point either escape or become followers, acolytes, enablers.

The narcissistic teacher has opportunities for mischief similar to that available to the preacher — the audience is often composed of young, impressionable minds who haven't learned skepticism or the ability to detect inconsistencies or self-absorption in a teacher. And in the very worst case, by the time the students acquire this ability, they might be living in a commune in South America, being offered funny-tasting grape juice.

Without deep study and patience, an effective teacher-student relationship is sometimes difficult to judge. The very best teachers, those most effective at inspiring a lifelong taste for knowledge, may be so unorthodox in their methods that an observer may wrongly suspect a narcissistic motive. For example, Nobel Prizewinner Richard Feynman is generally regarded to have been an excellent teacher and lecturer, but I wouldn't be surprised if someone who was unaware of his accomplishments and reputation, who happened to sit in on his lectures at Cal Tech and heard someone who sounded like nothing so much as a Brooklyn cabdriver talking about various esoteric topics, might draw an entirely mistaken conclusion.

What is unfortunate about modern education is that self-teaching is almost universally disparaged in favor of mass education, where as many as thirty or forty students are expected to learn the same material in the same way and at the same pace. This arrangement is virtually guaranteed to turn off any students not near the center of the bell curve. For example, talented and gifted students are often wrongly judged to be mentally handicapped by ... narcissistic teachers, people constitutionally incapable of imagining a student with needs that teacher cannot meet.

The Expert

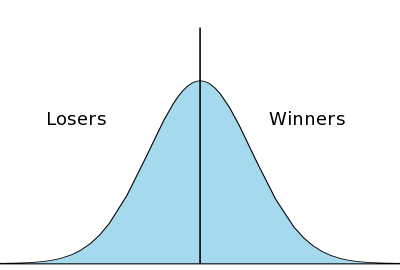

Standard Distribution

Standard DistributionThis is a broad, general category, attractive to narcissists for the reason that it is trivial to posture as an expert in something. I've decided to use the example of an investment advisor, a particularly fraudulent profession and haven for narcissists.

I've known a lot of investment advisors during my life. I began with an instinctive distrust, but without a firm theoretical understanding of why advisors can't be trusted. More recently, after a lot of mathematics and computer modeling, I know why they can't be trusted, and why so many narcissists get into the field.

The equities market is a perfect example where Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems place firm limits on what can be reliably said about it. If someone makes a remark about the equities market, and if investors think that person merits their attention, whatever he says will either become true or false beyond his wildest expectations within the hour, solely because people acted on his advice.

As just one example, in December 1996 former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan gave a speech at the American Enterprise Institute in which he described investors as suffering from "irrational exuberance." Within a few hours of Greenspan's speech, stocks fell worldwide. Greenspan's position as Fed chairman gave an unreasonable weight to an offhand comment, and many investors reacted as though they heard God clearing his throat. Greenspan resolved never to utter those words again.

The equities market is easily manipulated by self-proclaimed "experts" who often claim to have an inside track on where the market is going. This claim can be defended in a number of equally meaningless ways. One way is to say your investments did better than a popular market index like the Dow-Jones Industrial Average (hereafter DJIA), an index of typical stocks meant to provide a sense of the average market. But this claim is silly — given that the DJIA represents the portfolio of an average investor, fully 50% of investors are to the right of the average (the vertical line in the "Standard Distribution" graphic on this page), and 50% to the left (which is why they call it an average). Those on the left (who didn't do as well as the average) might blame the outcome on bad luck. Those on the right, who did better than the average, might decide to start telling other people how to invest their money.

But the silliness gets deeper. Someone might say he made millions with a small initial investment and his performance can't possibly result from luck. But those outcomes can, and usually do, result from luck. I just performed a computer simulation with these conditions:

(click here for the simulation's C++ source listing)

- Investors: 100,000

- Initial investment: $10,000

- Simulation time: 20 years

- Market overall growth: 12% per year

- Maximum price fluctuation per week: 5%

- Buy & hold investor outcome: $109,927.40

- Best performance: $4.6 million

- Number of new millionaires: 224

- Winners: 32,217 (32%)

- Losers: 67,783 (68%)

Please carefully examine these results. If you wanted to talk someone into hiring an advisor, you might point out that the best-performing portfolio made $4.6 million, compared to only about $110,000 for an unchanging, "buy & hold" portfolio, and there were 224 new millionaires. But if you were an honest person, not a narcissist, you would point out that 2/3 of those who hired advisors came out behind the market average.

In this simulation, the overall market grows in value 12% per year, which is the historical average value excluding the Great Depression. And I gave the active-portfolio investors every break — for example I didn't charge them brokerage fees for their weekly trades. Even with this break, 2/3 of the investors with active portfolios came out behind the DJIA and the buy & hold investor. In the real world, active investors pay for the privilege of falling behind the market average.

This result seems to contradict common sense — if prices go up and down with equal probability, why should there be more losers than winners among active traders? It's because of a "doldrum effect" (caused by a declining portfolio balance) that takes over when you are on the left side of the standard distribution — once you're on the left, it becomes increasingly difficult to get back to the right, even if you aren't paying brokerage fees and even as the market's average value continues to rise. This effect is a well-known secret among investment advisors.

But a statistically tiny percentage (0.2%) of investors come out way, way ahead. The best-performing portfolio made $4.6 million, in twenty years, starting with ten thousand dollars. Overall the simulation created 224 millionaires. How did it do this? Simple — it generated random numbers — by flipping a fair coin, so to speak. If the coin came up heads, that portfolio went up slightly, if tails it went down, but randomly.

I want to emphasize the point that this simulation creates all its results using random choices, not any kind of trading strategy. Random choices can and do produce occasional millionaires in a large pool of investors. As to a particular investor's claim that his portfolio's performance resulted from strategy and genius, remember Occam's Razor, the precept that the simplest explanation tends to be the right one. In this case, the simplest explanation is chance, not genius.

This simulation reveals some important things about the real equities market:

- Because the market is a living organism composed of millions of businesses and investors desperately trying to outsmart each other, there is no reliable way to predict its direction — except by trading on inside information, which is illegal.

- If someone comes out ahead or behind the market average, this result most likely arises from chance.

- People who hire investment advisors to manage their portfolios do less well on average than a boring buy & hold investor. This is true about reality as well as the simulation.

- Investment advisors will not reveal this fact, instead they will tell you a story about someone who made $4.6 million.

- This is because investment advisors are usually narcissists.

Turning now to the topic of market advice, here are some points an advisor might make about an "investment opportunity":

- "This stock is on the move! It's doubled in value over the past 12 months."

- "An important Wall Street guru has given this stock a 'buy' recommendation."

- "To prove my sincerity, I have personally taken a position in this stock."

Guess what, dear reader? Each of these statements is a good reason not to invest in that stock. Here's why:

- A stock that has doubled in value in 12 months is way ahead of the market average and isn't statistically likely to continue that pattern of growth, in fact, a "correction" is more likely, which means your investment might follow the stock down to a more realistic price.

- By the time a Wall Street guru speaks and you hear him, that train has left the station. People might already be unloading the stock, and the advice is less than worthless. There is a Wall Street saying about this: "buy on the rumor, sell on the news."

- If your investment advisor has a position in a stock, this represents a conflict of interest — he stands to gain personally with each new investment in that stock. And he intends to charge you for this advice — that's narcissism defined.

I can't think of a field of human endeavor with more public stupidity and narcissism than investment advisors and their clients. Well, okay, religion, but religious followers don't normally think of themselves as the sharpest knives in the drawer, but for some reason equities investors and advisors tend to picture themselves as great geniuses.

Investment counseling is an amazing field — you can tell the most transparent lies, and people will listen raptly and then pay you for the advice. It's a wonder that clinical narcissists don't abandon religion and enter this field instead.

References

| Home | | Psychology | | Children of Narcissus | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |