Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Psychology | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

Copyright © 2011, Paul Lutus — Message Page

(double-click any word to see its definition)

A note about terminology. In this article, to avoid excessive wordiness the term "psychology" refers to both psychiatry and clinical psychology. Psychiatry and clinical psychology are distinct fields, but have common properties — they're both based in human psychology, and they're equally unscientific.Introduction

HistoryA revolution is taking place in the world of human psychology1. Before the revolution, psychology relied on untested, sometimes untestable assumptions about an abstraction called the mind, and science had no important role. After the revolution, there will be a new science where psychology now stands.

In a recent Scientific American article entitled "Faulty Circuits"2, Thomas Insel, director of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), describes recent efforts to bring an evidence-based, scientific perspective to the diagnosis and treatment of psychological ailments. Insel says, "From the scientific standpoint, it is difficult to find a precedent in medicine for what is beginning to happen in psychiatry. The intellectual basis of this field is shifting from one discipline, based on subjective 'mental' phenomena, to another, neuroscience. Indeed, today’s developing science-based understanding of mental illness very likely will revolutionize prevention and treatment and bring real and lasting relief to millions of people worldwide."

I ask my readers to think about what the above quotation means. Because government health officials are understandably reluctant to take radical positions or climb out on limbs, the above quote represents a conservative view of the present state of human psychology — it's being actively considered for replacement by more effective, evidence-based methods from other fields, primarily neuroscience.

We're witnessing a fundamental change — a sweeping reëvaluation of psychology's content, interpretation and methods. Until recently clinical psychologists have attempted to diagnose and treat what are called "mental illnesses"3, which by definition are behaviors that originate in psychological abnormalities or "mental states", and are therefore addressable using psychological methods. But in recent decades, strong evidence has begun to suggest that what we call mental illnesses are actually symptoms of physical illnesses, and any meaningful diagnoses and treatments will require an understanding of the physical conditions that produce those symptoms.

Psychologists have recently begun to experience great pressure to abandon subjective clinical evaluations and treatments in favor of evidence-based methods — methods that require objective criteria to establish a diagnosis or choose a treatment. But many psychologists have objected to these pressures4, arguing that such a change would expose them to the risk of malpractice lawsuits. Of course, they are right — if a mental illness can be objectively diagnosed and effectively treated, then the possibility of a clinical failure would exist for the first time. (Under the present system, because there's no objective measure of success, there's no measure of failure, and no one can be held to account.)

But there is a much more compelling reason for clinical psychologists to resist evidence-based methods, and it's a reason many do not fully appreciate — the possibility exists that there are no mental illnesses, at least as that term was once defined:

Mental illness (old definition): An abnormal, debilitating condition originating solely in the mind, reliably diagnosable using psychological methods, and successfully treatable using psychological techniques.Most modern definitions of "mental illness" don't agree with the above traditional one — many now include the possibility that some mental illnesses have causes and remedies apart from psychological ones, but to date the implications of that fact haven't significantly changed clinical practice.

In this article I will show that, until now, psychology has operated under an assumption for which there was and is little evidence, and that we are in the midst of a complete change in the understanding of mental illness. I will show that the end result of the present revolution will be the abandonment of psychology and its replacement with a new branch of medicine with objective diagnoses and treatments. The bad news is that — yes! — the new practitioners might get sued for clinical misbehaviors. The good news it that this will become true only because there will be objective diagnoses and treatments that actually work.

I predict that the present revolution will succeed for the best of reasons — the ascendancy of reason over belief — and twenty years from now an evidence-based medical discipline will have replaced psychology. The latter will continue to exist but will be ranked alongside astrology.

I have one more prediction: all the conditions we now believe to be mental illnesses will either be reclassified as physical illnesses with mental symptoms, or will be recognized as behaviors not meriting the label "mental illness." In short, what we now think of as mental illness as defined above, will be exposed as a myth.

ScienceHow did we get here? At a time when scientific methods have become the preferred approach to medical diagnosis and treatment, how is it that an unscientific practice like psychology is the default treatment option for ailments with a psychological dimension? The answer is that until recently many illnesses with psychological symptoms have been difficult to diagnose, and some simply aren't treatable. Only recently have diagnostic tools and methods begun to be developed that have some chance to objectively identify diseases in this class.

This is not to say there has been no progress in reclassifying "mental illnesses." Schizophrenia and autism, once blamed on incompetent parenting or "refrigerator moms"5 and therefore amenable to psychological treatment, are now understood to be physical illnesses with psychological symptoms, and research continues into the origins and specifics of these physical diseases. Indeed, the examples of schizophrenia and autism, and increasing evidence in the case of other conditions, have led many in the mental health field to suggest that all conditions now thought to be "mental illnesses" are in fact physical illnesses with mental symptoms.

For decades there has been increasing evidence that psychologists can't reliably diagnose or treat mental illnesses, or mental illnesses aren't objective illnesses as that term is understood, or that psychology has no testable scientific content. Psychologists' reaction to this long-term trend has been to add more human behaviors to the "mental illness" category, in order not to lose more ground to medicine. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)5, what many call the "Bible" of psychology and its single most important guide to practice, shows this trend clearly — each new edition contains more conditions thought to merit the label "mental illness." Here is a count of "mental illnesses" included in the DSM by year:

Year Number of mental illnesses 1952 112 1968 163 1980 224 1987 253 1994 374 Obviously this trend might reflect an increase in our understanding of mental illness, and there might really be hundreds of legitimate mental illnesses. But let's take a closer look at some conditions listed in the current DSM, conditions thought to require intervention by a mental health professional:

- Stuttering

- Spelling Disorder

- Written Expression Disorder

- Mathematics Disorder

- Caffeine Intoxication/Withdrawal

- Nicotine use/Withdrawal

- Sibling Rivalry Disorder

- Phase of Life Problem

Hmm. It seems if you don't like your older brother, or can't spell or do math very well, you aren't just growing up, you're suffering from a mental illness and need help from a professional. But I favor another explanation — as time passed and psychiatrists and psychologists realized they couldn't reliably diagnose or cure real mental illnesses, they decided to repurpose themselves as academic tutors, babysitters and hired friends for wealthy patrons. For this strategy to work, the DSM needed to include ordinary states of being that could only justify the help of a teacher or sympathetic friend. In other words, in rewriting their profession's guidebook, for self-serving reasons psychologists deliberately blurred the distinction between everyday problems and mental illness.

My readers may wonder why a parent would hire a costly, overqualified mental health professional to teach his child how to add columns of figures — isn't that unnecessarily expensive compared to a teacher? Not necessarily — because mathematical ineptitude has been reclassified as a mental illness, an insurance company may be required to pay for the treatments, or a school district may be forced by statute to cover the cost of this essential therapy.

Modern psychology is perfectly aligned with the needs of contemporary western society — people frequently move from place to place, have few long-term friends, and almost no one lives in a small village where people know each other and are ready to listen. This often means people have no ready options to deal with the pressures of life. But there are psychologists everywhere — they're more than willing to listen to you, they possess an air of faux scientific respectability compared to a religious figure, and your health-insurance company might even be maneuvered into paying for treatments. And best of all, there is virtually nothing you might talk about that isn't seen as a legitimate mental illness — if you believe you have been abducted by aliens, or you believe yourself to be reincarnated and want to discuss the unresolved issues of your past lives, psychologists are ready to agree with you and listen sympathetically6,7.

Psychology's Success StoryScience has always been a problem for psychology, but because of the increasing acceptance of scientific standards elsewhere in society, psychology is about to be overwhelmed by its inability to adopt scientific standards.

In a medical context, defining science is surprisingly easy — a specific medical practice either pays attention to evidence or it doesn't. That principle leads to this sequence:

- Science mandates that evidence — objective observation and measurement — replace opinion and subjective judgments.

- The presence of evidence allows the shaping of general theories based on the evidence.

- The presence of theories allows objective tests in different contexts to assess their validity.

- The possibility of failure in such tests admits the possibility that a theory — or a field — may be falsified and abandoned.

As it turns out, falsifiability — the possibility that a theory might be discovered to be false — is what separates science from opinion8. Without the possibility of falsification, invalid theories cannot be replaced by valid ones, and reason cannot prevail over belief. Without the possibility of falsification, science loses all meaning.

Let's look at examples of how science works in mainstream medicine, and in psychology.Medicine:

During the 1952 polio epidemic, 58,000 people became victims of this cruel disease — a number roughly equal to the death toll for the 16-year Vietnam War, but within a period of months. In 1955, Jonas Salk9 announced the creation of a vaccine against polio, the outcome of a seven-year research program into the nature of the virus responsible for polio.

The polio vaccine research program was a classic of its kind — moving from theoretical work to field tests with volunteers, Salk performed all the steps in, and took all the precautions required of, a scientific project involving human subjects. Polio was an ideal target for scientific methods — its manifestations were unambiguous (many people died or became paralyzed) and a cure would be equally unambiguous. More important, there was no question about the cause of the disease — the virus could be detected directly, and the vaccine was created with this specific virus in mind.

In summary, polio was an objective and dangerous disease, the science and technology to create a vaccine was successfully applied, the vaccine was not applied until it was proven effective, and polio has become a historical artifact.

Psychology:

In 1944, Hans Asperger10 published the first description of what has come to be known as Asperger Syndrome11. As originally described, the syndrome was characterized by "a lack of empathy, little ability to form friendships, one-sided conversations, intense absorption in a special interest, and clumsy movements." Interest in Asperger Syndrome didn't really take off until it was included in the DSM in 1994, after which the number of diagnoses exploded.

Unfortunately, the symptoms of Asperger Syndrome are difficult to distinguish from the spectrum of normal behaviors in young people, and for self-serving reasons psychologists have begun to diagnose Asperger Syndrome at the suggestion of parents, rather than on the basis of objective diagnostic evaluations. One might wonder why a parent would want this diagnosis — isn't a mental illness universally stigmatizing and undesirable? Well, as it turns out, Asperger Syndrome has begun to seem rather attractive to a particular, twisted kind of parent, on the ground that many famous, accomplished people have been given the Asperger label — Thomas Jefferson, Albert Einstein, Bill Gates, and Hans Asperger himself.

Also, there are mental conditions in parents that find a perfect expression in the pursuit of dubious mental diagnoses in their children, primarily variations on what is known as "Münchausen syndrome by proxy" (MSP)12. For such a parent, an Asperger diagnosis is essentially perfect — it meets the parents' psychological needs, while not doing much lasting harm to the child. Unlike Asperger Syndrome, which has always been a problematic diagnosis, MSP is unambiguous — parents (usually mothers) who suffer from this condition, and whose children are taken to a hospital and protective custody, are sometimes observed slipping into the hospital to poison their own children.

There are a number of serious problems with Asperger Syndrome as a diagnostic category:

- It is nearly impossible to diagnose accurately, indeed statistics show that about 20% of those given the diagnosis later "grow out of it" and show no symptoms as adults, which admits the possibility that they were misdiagnosed in the first place. Also there have been many reports of opportunistic diagnosis of this syndrome in people who were simply different than their peers.

- Over time, psychologists have begun to pay attention to the behavior of those given the diagnosis, rather than published diagnostic criteria, which has had the effect of turning Asperger Syndrome identification into a hopelessly self-referential process rather than a clearly defined diagnosis.

- Parents can have any number of reasons for wanting this diagnosis, including placing their children in the company of some very successful people, drawing attention to themselves as burdened but skilled parents of difficult children, or, in the case of Münchausen syndrome by proxy sufferers, a wish to acquire the diagnosis rooted in their own profound dysfunctions rather than anything resembling mental illness in their children.

The above points show how a hypothetical syndrome, one with no objective diagnostic criteria and no treatment, was uncritically adopted by psychologists and resulted in an epidemic of diagnoses in advance of any scientific effort to find out if it referred to anything real. The epidemic of diagnoses resulted from unethical psychologists who either assigned the diagnosis for personal gain, or felt pressured by parents with one or another reason for wanting the diagnosis for their children — everything but objective diagnostic criteria on which everyone agrees.

As a result of these abuses, the DSM's editors have reluctantly decided to remove Asperger Syndrome from the next edition of the DSM13, and advise people that it has no clear meaning and should not be offered as a diagnosis.

In summary, Asperger Syndrome, resulting from the subjective observations of one practitioner, became popular after being included in the field's diagnostic guide. This acceptance caused widespread abuse, and the syndrome is now being removed and discredited, but without ever being studied scientifically.

I emphasize that the example above, Asperger Syndrome, is one of dozens of terrible examples of unscientific beliefs that were uncritically adopted by psychologists, put into clinical practice, and then reluctantly abandoned after public outrage or embarrassing incidents that reflected poorly on psychology.14

The role of evidence

Scientific fields that offer treatments, for example mainstream medicine, must validate them in advance of offering them in a clinical setting. The rules governing introduction of a new treatment are very strict, and depend on ongoing medical research, both for new treatments and ongoing evaluation of treatments that are already part of clinical practice. All this depends on scientific discipline and rigor — above all, the priority of evidence and a willingness to abandon falsified theories.

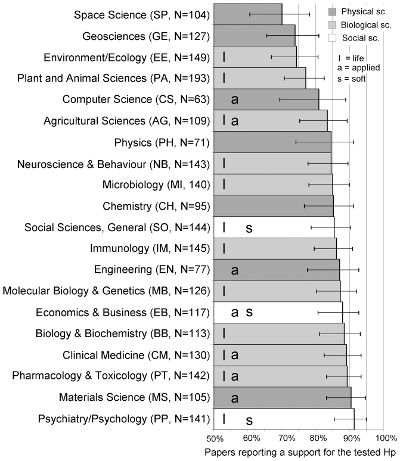

Figure 1: Positive Results by Discipline

Figure 1: Positive Results by Discipline

Image courtesy PLoS OneOne important test of a field's scientific integrity is the number of theories that are discovered to be false and publicly abandoned. For a disciplined field guided by evidence, one would expect to see publication of a mixture of experimental outcomes — some with positive results, some negative.

As it turns out, a measure of a field's standing among sciences is the number of negative experimental outcomes that are published. In this connection it's very important to say that, in science, there are no failed experiments — each experiment's outcome, positive or negative, contributes to our understanding of nature.

Of all scientific disciplines, it seems psychology consistently has the poorest publication rate for negative outcomes. In a recent study, space science (the best performer) published 29.8% negative outcomes, while psychology published only 8.5% (see Figure 1). The reasons for this are well-established — because scientific standards are so weak in psychology, researchers will simply not publish studies that don't live up to expectations, or as the results start coming in, they will change what they claim to be studying, and publish something else instead — anything to get a positive result.

How important is the publication of negative scientific outcomes? Well, it is very important — one famous experiment in physics should make the point. In 1887, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley performed an experiment15 to detect the ether, an essential component of the theory of the day. The experiment failed to detect the ether, this failure caused a reëvaluation of some basic assumptions about nature, and this ultimately led to Einstein's Theory of Relativity. If Michelson and Morley had not published their negative result, this would have set physics back, perhaps for decades.

Description vs. ExplanationIt seems the vast majority of psychology's beliefs and practices are eventually abandoned, after either being ridiculed from outside the field, exposed as frauds by the media, or by creating public outrage, as with Asperger Syndrome16, Facilitated Communications17, and Recovered Memory Therapy18 (these are only recent examples in a long list).

When faced with criticisms of the fluid nature of their practices, psychologists often respond by pointing out that Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)19 seems to have been studied scientifically and is shown to be effective. Unfortunately, some misguided psychologists have crossed the line and performed real science on CBT, and the results cast serious doubt on the prevailing belief.

In one study20, CBT was broken down into elements — the parts of CBT believed to contribute to its effectiveness — and the elements were applied separately, to see which of them produced the greatest benefit. Specifically, the study separated CBT into three subtherapies, one focusing on a method corresponding to a widely accepted protocol (Beck21), one focusing on behavioral activation, and one focusing on coping skills.

At the end of this carefully designed twenty-week study and to the surprise of the researchers, there was no difference between the experimental subgroups — all fared equally well. This discouraging outcome supports something called the "Dodo bird verdict"22, the idea that (to put it very simply) specific therapies don't change the outcome, only the fact that someone is willing to listen to the client.

In another study23, it was discovered that the majority of CBT's therapeutic benefit took place in the first few sessions, before introduction of those elements that distinguish CBT from other therapies. This outcome favors the idea that therapies do not differ in a consistent, measurable way, and therefore the outcome can be attributed to both the Dodo bird verdict and the Placebo Effect24.

A number of studies25,26 including a meta-analysis27 of many studies of CBT, show that, when systematic biases are adjusted for, CBT's imagined superiority over other therapies evaporates. All these studies support the idea that psychological treatments cannot be distinguished from each other or from the Placebo Effect.

In his book "Manufacturing Depression"28, psychotherapist Gary Greenberg describes CBT as "a method of indoctrination into the pieties of American optimism, an ideology as much as a medical treatment." To paraphrase Greenberg, he describes CBT as one component in a strategy hatched by psychology and the drug industry — by offering a range of treatments including drugs and therapy, and by relying on the public's perception of psychology as a science, they have succeeded in turning what may be an ordinary emotional state into a mental illness with a diagnosis and a cure.

This is not to discount the possibility that depression is sometimes distinct from the blues, and may be treatable, but because of the above process and because of the sometimes lucrative nature of mental illnesses, depression has become more an industry than a mental illness.

There is an element of circular reasoning in the creation of a new mental illness, as true for depression as it was for Asperger Syndrome. Certain elements must be present for a behavior or mental state to attain the status of a mental illness, and these elements ideally reinforce each other:

- Depression is not a normal emotional state — "the blues" — it is a mental illness because there is a diagnosis and there is a cure.

- The diagnosis of depression is complex and requires professional evaluation.

- The cure for depression is a combination of drugs and therapy.

The logic works like this: if there were no drugs specifically meant to treat the disease of depression, or if there were no therapies that are known to "cure" the disease of depression, then people might reasonably wonder whether depression merits its present standing as a disease, a mental illness.

Because of increasing pressure from mainstream medicine and society to adopt evidence-based practices, psychology has begun to test its own assumptions and therapies. But by opening their assumptions up to critical evaluation, psychologists are discovering there is no evidentiary basis for asserting the superiority of one treatment over another. This in turn allows the explanation that psychological treatments may be demonstrations of the Placebo Effect29, not of targeted, unique therapies of proven efficacy, and people may derive the same benefit from conversations with a sympathetic friend.

ConclusionPsychology shares a defect in common with the other so-called "soft sciences" — it is satisfied to describe things it cannot explain. The primary problem with a reliance on description with no explanations, is that such a field has no depth and no basis for intellectual growth. This is why psychology's history is punctuated by fads, each hailed as a breakthrough, each eventually abandoned after its defects became obvious — psychoanalysis, various novel therapies, lobotomy30, schizophrenia and autism blamed on refrigerator moms31, Recovered Memory Therapy32, Facilitated Communications33, Asperger Syndrome34.

But there's a more basic problem with a field that relies only on descriptions — it cannot become a full-fledged science. True science has certain essential properties that conflict with the description-only model:

- Mere descriptions cannot be falsified, and cannot be used as the basis for broad, general statements, or "theories".

- A field becomes scientific by shaping theories that generalize particular observations, that endeavor to explain what has been observed.

- If a theory's general principles are validated in different domains, those theories end up defining the field.

- Scientific theories must in principle be falsifiable by comparison with new evidence.

- The more general a theory is, the more subject to falsification it becomes. A statement about one rock cannot be meaningfully falsified, but a statement about all rocks certainly can — one need only find an exception in the set of all rocks.

My readers will not be surprised to discover that psychology relies entirely on description, rarely tries to explain, shapes few theories, and is immune to falsification. This is one of a list of reasons for the present revolution:

- Diagnostic advances in mainstream medicine, and neuroscience in particular, that have created an overlap with psychology's territory.

- The many conditions formerly thought to be psychological diseases — "mental illnesses" — but now known to be physical diseases with psychological symptoms.

- A strong scientific tradition in mainstream medicine and a willingness to put forth testable explanations, not just descriptions.

- Increasing resistance on the part of physicians and managed-care companies to pay for ill-defined diagnoses and treatments for conditions with no concept of a cure.

Again, the primary obstacle to the continued existence of psychology in its present form is that, to put it bluntly, there may not be any mental illnesses35 — all the conditions presently thought to be mental illnesses may be either physical ailments with psychological symptoms (as with schizophrenia and bipolar syndrome), or states within the spectrum of normal human behaviors.

FeedbackThere is a historical parallel for what is happening in psychology. Before the birth of observational astronomy, there was a mixture of beliefs and superstitions, now called astrology, that tried to satisfy people's curiosity about the heavens and offer completely bogus personal guidance as a sideline. In astrology, people's lives are ruled by the mysterious heavens. In the same way, in psychology, people's lives are ruled by the mysterious mind. In neither case are people expected to accept personal responsibility or rethink their assumptions.

Observational astronomy developed into a science and proved that astrology is bunk, but this didn't prevent astrologers from practicing their trade, and today, it's estimated there are ten astrologers for every astronomer — and the astrologers often make more money appealing to superstition than astronomers make appealing to reason — just as with psychology.

The historical parallel will likely continue. Neuroscience will continue to reclassify mental illnesses as physical ones, offer cures in some but not all cases, and will produce scientific explanations to replace psychology's ever-changing descriptions. Eventually neuroscience will replace psychology in the thinking of educated people, but this won't prevent psychologists from continuing to appeal to the needs of the uneducated and weak-minded — just as with astrology.

Neuroscience certainly won't be a panacea, for the reason that many diseases with a psychological component have their roots in genetics, in which case the only "cure" is euphemistically called "genetic counseling," i.e. the advice not to have children. But at least we will have explanations for diseases now only described.

Once neuroscience establishes a firm track record as a science, a subtle but important perceptual shift will take place, and people will expect and demand explanations where today they're willing to accept descriptions. At that moment, at least among educated people, psychology will for the first time be seen for what it is — just as with astrology.

Footnotes

- In this article, the terms "psychology" and "human psychology" are a convenient shorthand to refer to clinical and experimental psychology, and psychiatry — all the fields and subfields that deal with subjective mental states, diagnoses and treatments.

- Faulty Circuits (Insel [director, National Institutes of Mental Health], Scientific American, April 2010): "From the scientific standpoint, it is difficult to find a precedent in medicine for what is beginning to happen in psychiatry. The intellectual basis of this field is shifting from one discipline, based on subjective 'mental' phenomena, to another, neuroscience. Indeed, today’s developing science-based understanding of mental illness very likely will revolutionize prevention and treatment and bring real and lasting relief to millions of people worldwide."

- Mental illness (old definition): An abnormal, debilitating condition originating solely in the mind, reliably diagnosable using psychological methods, and successfully treatable using psychological techniques.

- Evidence-based Practice in Psychology (Levant [APA president], American Psychological Association, February 2005): "Some APA members have asked me why I have chosen to sponsor an APA Presidential Initiative on Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in Psychology, expressing fears that the results might be used against psychologists by managed-care companies and malpractice lawyers ... psychology needs to define EBP in psychology or it will be defined for us. We cannot afford to sit on the sidelines."

- Refrigerator mother (Wikipedia): "The term refrigerator mother was coined around 1950 as a label for mothers of children diagnosed with autism or schizophrenia. These mothers were often blamed for their children's atypical behavior"

- John Mack, psychiatrist, professor, Harvard Medical School: "... a leading authority on the spiritual or transformational effects of alleged alien abduction experiences"

- Ian Stevenson, professor of psychiatry, University of Virginia: "... considered that the concept of reincarnation might supplement those of heredity and environment in helping modern medicine to understand aspects of human behavior and development."

- Falsifiability (Wikipedia): "... the logical possibility that an assertion could be shown false by a particular observation or physical experiment. That something is 'falsifiable' does not mean it is false; rather, it means that if the statement were false, then its falsehood could be demonstrated."

- Jonas Salk (Wikipedia): "...best known for his discovery and development of the first safe and effective polio vaccine."

- Hans Asperger (Wikipedia): The practitioner after whom Asperger's Syndrome is named.

- Asperger Syndrome (Wikipedia): A condition, now discredited, once thought to resemble high-functioning autism.

- Münchausen syndrome by proxy: "... a disorder in which a person deliberately causes injury or illness to another person (most often his/her child), usually to gain attention or some other benefit."

- A Vanishing Diagnosis (Wallis, New York Times, November 2, 2009): "Asperger’s means a lot of different things to different people ... It’s confusing and not terribly useful ... We don’t want to say that no one can ever use this word ... [but] It’s not an evidence-based term."

- Recovered memory therapy: A now-discredited practice in which clients were encouraged to "recall" suppressed memories of, among other things, childhood abuse. It resulted in many false accusations of sexual abuse. U.S. Courts have ruled they will no longer hear cases of this kind.

- Michelson–Morley experiment: A crucial failed experiment that falsified the idea of an ether and paved the way for Einstein's Theory of Relativity.

- A Vanishing Diagnosis (Wallis, New York Times, November 2, 2009): "Asperger’s means a lot of different things to different people ... It’s confusing and not terribly useful ... We don’t want to say that no one can ever use this word ... [but] It’s not an evidence-based term."

- Facilitated communication: A now-discredited practice in which a "facilitator" assisted a disabled person in communicating in ways not possible for the disabled person alone. This practice has been largely abandoned after — you guessed it — the disabled person seemed to be reporting horrible sexual abuse, but the actual accusations originated with the "facilitator". Although thoroughly discredited, it is still practiced in some areas.

- Recovered memory therapy: A now-discredited practice in which clients were encouraged to "recall" suppressed memories of, among other things, childhood abuse. It resulted in many false accusations of sexual abuse. U.S. Courts have ruled they will no longer hear cases of this kind.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy: a psychotherapeutic approach that aims to solve problems concerning dysfunctional emotions, behaviors and cognitions through a goal-oriented, systematic procedure.

- A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression: "... , both BA and AT treatments were just as effective as CT at altering negative thinking as well as dysfunctional attributional styles."

- Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research: Proponents of CBT.

- Dodo bird verdict: " ... the theory that the specific techniques that are applied in different types and schools of psychotherapy serve a very limited purpose."

- Establishing Specificity in Psychotherapy Scientifically: Design and Evidence Issues: "... the uniform efficacy of psychotherapeutic treatments with adults does not provide any evidence that the null hypothesis is false."

- Placebo Effect: The observation that placebos (treatments of no real efficacy) produce benefits for purely psychological reasons.

- A meta-(re)analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy versus 'other therapies' for depression: "The results of this study fail to support the superiority of CT for depression. On the contrary, these results support the conclusion that all bona fide psychological treatments for depression are equally efficacious."

- The effectiveness of psychotherapy: "... no specific modality of psychotherapy did better than any other for any disorder; psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers did not differ in their effectiveness as treaters; and all did better than marriage counselors and long-term family doctoring."

- Treating depression with the evidence-based psychotherapies: a critique of the evidence: "... the specificity of CBT and IPT treatments for depression has yet to be demonstrated."

- Manufacturing Depression: The Secret History of a Modern Disease: Gary Greenberg, author and psychotherapist.

- Placebo Effect: The observation that placebos (treatments of no real efficacy) produce benefits for purely psychological reasons.

- Lobotomy: "... consists of cutting the connections to and from the prefrontal cortex, the anterior part of the frontal lobes of the brain."

- Refrigerator mother (Wikipedia): "The term refrigerator mother was coined around 1950 as a label for mothers of children diagnosed with autism or schizophrenia. These mothers were often blamed for their children's atypical behavior"

- Recovered memory therapy: A now-discredited practice in which clients were encouraged to "recall" suppressed memories of, among other things, childhood abuse. It resulted in many false accusations of sexual abuse. U.S. Courts have ruled they will no longer hear cases of this kind.

- Facilitated communication: A now-discredited practice in which a "facilitator" assisted a disabled person in communicating in ways not possible for the disabled person alone. This practice has been largely abandoned after — you guessed it — the disabled person seemed to be reporting horrible sexual abuse, but the actual accusations originated with the "facilitator". Although thoroughly discredited, it is still practiced in some areas.

- A Vanishing Diagnosis (Wallis, New York Times, November 2, 2009): "Asperger’s means a lot of different things to different people ... It’s confusing and not terribly useful ... We don’t want to say that no one can ever use this word ... [but] It’s not an evidence-based term."

- Mental illness (old definition): An abnormal, debilitating condition originating solely in the mind, reliably diagnosable using psychological methods, and successfully treatable using psychological techniques.

| Home | | Psychology | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |