Braking Distance

Question: if a car going 20 miles per hour (MPH) requires 20 feet to stop, how much distance is required at 40 MPH?

- 10 feet.

- 20 feet.

- 40 feet.

- 80 feet.

The answer, which surprises nearly everyone, is (d) 80 feet (on dry, level pavement and neglecting driver reaction distance). This is because the energy of a moving car is proportional to its mass times the square of its velocity, based on the kinetic energy equation from physics:

\begin{equation}

\displaystyle E_k = \frac{1}{2} m v^2

\end{equation}

Where:

- $E_k$ = Kinetic energy, joules

- $m$ = Mass, kilograms

- $v$ = Velocity, meters/second

It turns out that a car's braking distance is proportional to its kinetic energy. The energy is dissipated as heat in the brakes, in the tires and on the road surface — more energy requires more braking distance. This explains why braking distance increases as the square of a car's speed.

Stopping Distance Equation

We can use the kinetic energy idea, and a knowledge of driver reaction times, to write an equation that predicts car stopping distances ("stopping" distance is the sum of reaction and braking distance). Here is the equation's canonical form:

\begin{equation}

d = r v \frac{10}{36} + \frac{v^2}{b}

\end{equation}

Where:

- $d$ = Total stopping distance (reaction + braking), meters.

- $v$ = Vehicle speed, kilometers/hour.

- $r$ = Driver reaction time, seconds.

- $b$ = Braking coefficient factor.

Notes:

- The left-hand side of the equation ($r v \frac{10}{36}$) converts the driver's reaction time into distance traveled during that time.

- The right-hand side of the equation ($\frac{v^2}{b}$) computes braking distance by applying a braking coefficient factor ($b$) to the square of the car's velocity. Assuming dry, level pavement, a typical value for $b$ would be 170, but this is an empirical factor — it's derived from field measurements.

- This equation may be rewritten for non-metric measurement units, but it's simpler and more reliable to convert its arguments and results to/from metric units:

- To convert input velocities from miles per hour (MPH) to KPH, multiply by 1.609344.

- To convert output distances from meters to feet, multiply by 3.28084.

- Remember that this equation provides the car's total stopping distance — the sum of driver reaction distance (left-hand side) and braking distance (right-hand side). To compute these values independently, isolate the equation's sides (driver reaction distance = $r v \frac{10}{36}$, braking distance = $\frac{v^2}{b}$).

Stopping Distance Tables

Here are tables of typical values generated using the above equation and that agree closely with data published by public safety organizations.

Metric units: (KPH, meters):

Imperial units (MPH, feet):

These tables assume dry, level pavement and a driver reaction time of 1.5 seconds. It turns out that, within broad limits and because of the physics of tire friction, the size of one's tires and their loading (from vehicle mass) don't significantly change the outcome for most vehicles (details below in the "Common Misconceptions" section), so the above tables provide reasonably accurate stopping-distance predictions — but the equation provided earlier is more flexible and useful than these tables.

Calculator

This calculator provides results for user-entered speeds, driver reaction times and braking coefficients. Choose input and output units and enter values in those units.

Common Misconceptions

Vehicle Mass

For a fixed tire size and within reasonable limits, increasing a vehicle's mass shouldn't increase its braking distance. The reason is that the heavier vehicle's tires apply more force to the road — braking effectiveness results from a combination of surface area and force. The increased inertia of the heavier vehicle is balanced by its increased surface force.

Tire Surface Area

At first glance, one might think increasing the size and road-contact surface area of a tire should improve its braking performance — after all, there's more rubber contacting the road. But as it turns out, for a given vehicle mass, each square meter of a larger tire's surface presses against the road with less force, and (as explained above) braking effectiveness results from a combination of surface area and force. This is why we don't see gigantic tires on the vehicles of safety-conscious drivers — it just doesn't work.

Moving in the other direction, if we make tires too small, the energy of braking would melt their surfaces, destroying their effectiveness. Also small tires tend to wear out more quickly in normal operation, so there's a lower practical limit to tire size.

Truck Braking Distance

Large truck operators often claim that a large truck must have more braking distance, because stopping a greater mass requires more distance. This is false, and I'm going to prove it below. Once you've read the proof, you will realize the big-truck braking-distance argument makes no sense. Here we go:

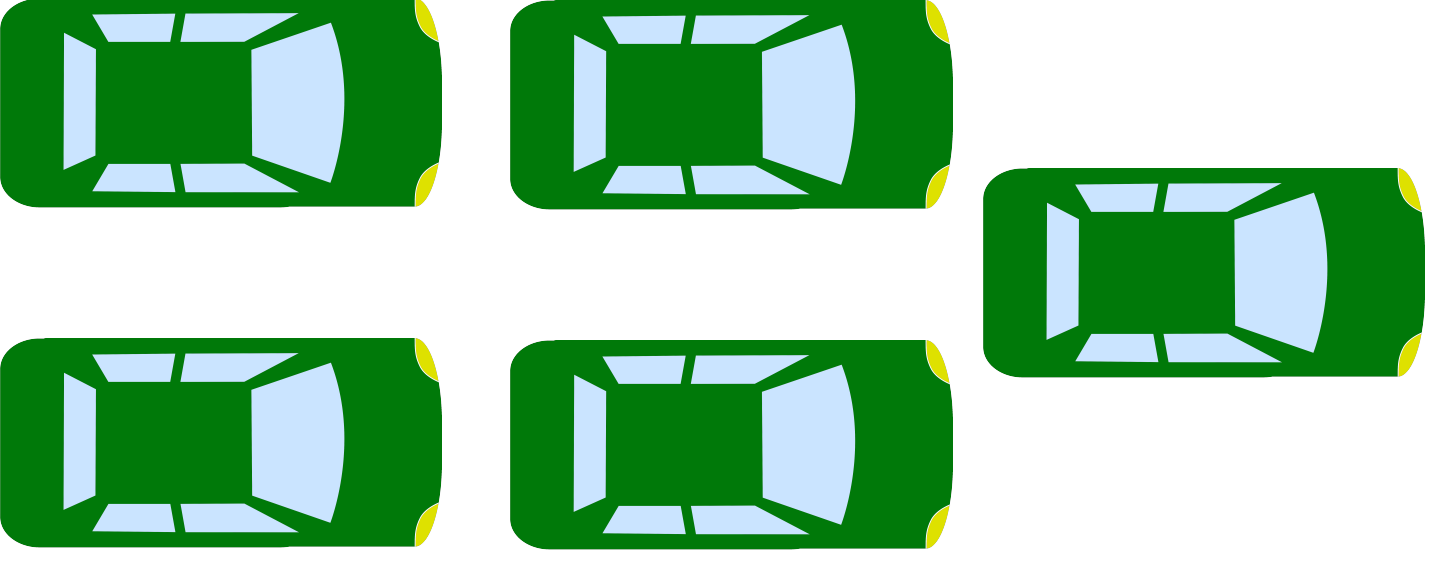

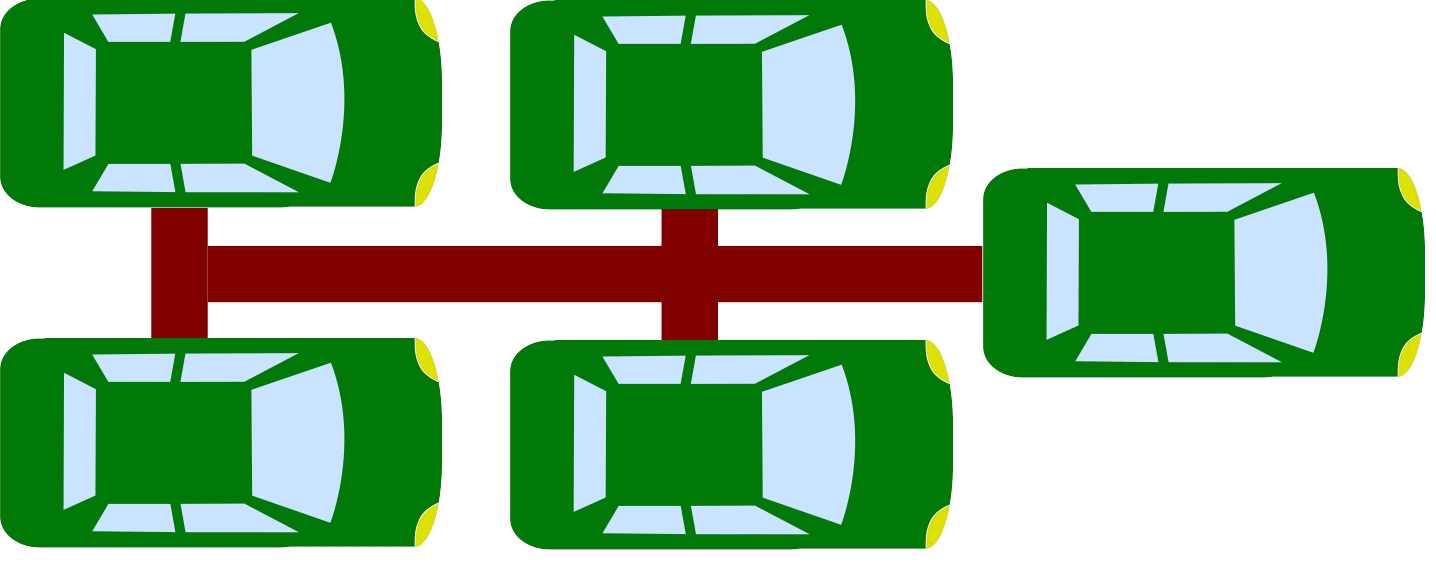

Imagine a sport-utility vehicle (SUV) that weighs four tons and has four tires. Its braking distance can be accurately predicted using the stopping distance equation provided earlier.

|

|

Compare the SUV with a big truck that weighs 20 tons and has 20 tires. Can this big, heavy truck — five times more massive than the SUV — stop in the same distance? Yes, it must be so — read on.

|

|

Now imagine five four-ton SUVs driving close together, almost touching. If they all apply their brakes at once, each SUV will stop in the same distance as when separated.

|

|

Now imagine the five SUVs are connected together by metal bars, so they become one vehicle — a vehicle that weighs 20 tons and has 20 tires. What has changed? Each driver applies his brakes in the same way, therefore the connected assembly of SUVs stops in the same distance that the individual SUVs do when separated.

By being connected, the five individual four-ton SUVs have become a vehicle that weighs 20 tons, has 20 tires, and stops in the same distance as one SUV.

Q.E.D.*

|

|

It's true that, in present-day reality, big trucks do require more stopping distance than small cars, but the reason is economics, not physics. In principle, big trucks could be designed to stop in the same distance as small cars, if we wanted to pay for the engineering improvements.

Conclusion

Here are this article's "take-homes":

- A car's braking distance increases as the square of its speed (disregarding reaction time). Twice as fast, four times the stopping distance.

- Heavy vehicles with adequate brakes should stop in the same distance as light vehicles, because the heavy vehicle's tires are either more numerous or are pressing down on the road with more force.

Ordinarily, not knowing physics and math is only inconvenient, but for car stopping problems it can get you killed.

Reader Feedback

Truck Stopping Distances

Thank you for your explanation of vehicular braking characteristics. It was interesting to read. However, I would like to refute your assertion that "big trucks" stop in the same distance as an SUV.

I look forward to a refutation that understands and acknowledges the underlying physics.

Your Comparison: (Compare the SUV with a big truck that weighs 20 tons and has 20 tires. Can this big, heavy truck — five times more massive than the SUV — stop in the same distance? Yes, it must be so — read on.)

A US Commercial Hauling truck (aka, tractor-trailer) is a vehicle with a combined Maximum GVW of 80,000 lbs. Typically they are loaded to 50,000 - 70,000 lbs GVW. There are special permits that can be obtained to exceed this weight with unmodified equipment. The truck and trailer can have a significant amount of weight variation. The braking systems are typically set up to be most effective at a mean value. Additionally, in your assertion, you state that the commercial truck has 20 tires on the ground. In fact, most have only 18.

Yes, and each of those 18 tires presses on the pavement with proportionally more force than one with 20 tires, so if the truck has adequate brakes, the braking distance is the same.

If the truck is loaded light or empty, the truck will tend to break traction more easily and cause an extended distance stop.

Wait ... so are you saying if the truck is lightly loaded, it requires more stopping distance, not less? Surely you see the contradiction in your argument — that if a truck is heavily loaded, it takes more distance to stop, but if it's lightly loaded, it also takes more distance to stop?

If the truck is loaded heavier than the adjust level, the greater energy will take longer to dissipate.

No, the higher kinetic energy is dissipated over the same distance because the tire pressure on the asphalt is proportionally greater — more heat is generated along the truck's path, but the stopping distance is the same. It all comes out in the physics — if the braking system is properly designed and the tires don't melt under high loads, the braking distance on dry, level pavement is the same. In my article I make this point with some number N of SUVs, but if you prefer I can add SUVs to equal the mass of any imaginable truck with any number of wheels.

Here's the take-home: If you increase a vehicle's mass with the same number of tires, each tire presses on the road with more force, so the stopping distance remains the same. If you decrease the vehicle's mass, the tires press down with less force, so the stopping distance remains the same. For the underlying physics and math, see my reference list at the bottom of this message.

So, the vehicle comparisons are not apples to apples.

If you had understood the key points in my article, you would realize that, for properly designed brakes, adequately sized tires and the same surface, all vehicles require the same stopping distance.

Basically, your 5 SUVs would be towing one extra SUV and minus a pair of wheels and trying to stop in the same distance.

Think about what you're saying. If I double the number of SUVs in my example, the braking distance is the same. If I instead load each SUV with more mass, their tires press on the pavement with more force, so they stop in the same distance.

Link: Does the braking distance of a car depend on weight of the car? (ResearchGate)

Quote: "The above equation shows that braking distance is independent of mass of vehicle."

Link: Stopping Distance for Auto (HyperPhysics)

Quote: "Note that this [equation] implies a stopping distance independent of vehicle mass."

And so on, for hundreds of references. Surely you don't think I made this up, do you? That would be incredibly irresponsible, and I could be held to account for the consequences.

I hope this helps, and thanks for writing.

Vehicle Stopping Distance in Inclement Conditions

Thank you for providing such clear explanation on stopping distance. It will definitely inform my writing.

Are aware of common additional factors that would be included in the case of rain or snow while driving? Certainly there are a large number of variables that cannot be easily tabulated outside of test conditions. I'm trying to discover if there is a general maxim that could be suggested about stopping in certain conditions.

Example - if it takes approximately 200 feet to stop an average car on clear, flat, dry pavement using average braking power, could we establish a corollary that generally describes the stopping distance for other conditions like "Because of the XYZ variables, driving in wet conditions requires 1.8 times the stopping distance as in dry"?

One cannot reliably do this. Consider the variables:

- The notorious combination of a pea-gravel surface and anti-lock brakes, the latter of which will glide over the gravel and apply almost no braking force, wrongly calculating that traction has been lost. This combination of factors must be experienced to be believed.

- The first season's rainfall over pavement coated with a full season of oil buildup from past traffic.

- New snow on top of a layer of old snow. When this happens in steep terrain, it leads to avalanches. When it happens on roadways, it leads to a false sense of security because the top snow layer looks fresh and pliable, but it hides a slick surface beneath.

- Black ice, very dangerous and often appearing when the air temperature is well above freezing because the pavement radiates its heat directly into space, disregarding the intervening air's temperature (in physics, radiation is much more efficient than convection).

- Irregular surfaces with patches of water and hydroplaning effects.

No, these conditions and others mean one cannot say with any certainty what a stopping distance will be on a surface other than dry, level pavement.

Braking Distance on a Slope

Thank you for the information on the mechanics of stopping distances for an average vehicle on a "level", dry surface, tires of average condition etc. But...how does the math/physics change if the surface isn't level but has a slope? Let say 10%. The mass of the vehicle isn't changed. How about the frictional forces?

First, for a slope s expressed as a percentage, the angle in degrees is equal to tan-1(s / 100), so for a 10% slope it's 5.71 degrees — call this θ.

The vertical component of the mass (that bears down on the tires and road surface) is on average m cos(θ) (m = vehicle mass), so for the 10% slope case, the effective frictional mass is 99.5% of the level mass. But the vehicle's inertial mass (working to prevent a change in velocity) remains the same. Therefore we already have a factor in the vertical dimension that works against an efficient stop.

Added to this is the effect of the slope. A force proportional to m sin(θ) is added to — or subtracted from — the forces acting on the vehicle and its tires. For 5.71 degrees this is roughly equal to 0.1 m. So for a downhill direction, the effective stopping distance from this factor alone is increased by 10%. I emphasize that this factor can't be evaluated independently of the prior factor ("vertical component"), which has the effect of reducing the vehicle's effective braking mass but without changing its inertial mass.

More formally, for intermediate angles between zero and 90 degrees, the math becomes very tricky because it also depends on the behavior of the car's suspension and its center of mass. The above equations are only applicable — and only approximately — for angles near zero.

All the above becomes practically unworkable if we try to calculate the specific effect on the four individual tires for a vehicle with a high center of mass (the tires nearer the center of mass get greater loading, those farther from the center of mass get less).

Going to the extreme, if a vehicle is in free fall (in a vacuum), there are no fictional forces so at that point it is removed from the equation completely, right?

Yes. At that point it's a classic falling object on a ballistic trajectory, no braking force any more. Interestingly, in an environment with less gravitational acceleration like the moon, masses can be lifted against gravity more easily, but they have the same inertia, so getting an object moving (applying an acceleration) on a level frictionless surface requires the same amount of force as on earth. The Apollo astronauts found it surprisingly difficult to adjust to having much less gravitational mass but the same inertial mass — some just fell over.

So how does the physics change for a 10% slope?

As above. In summary, a simple answer is not available. After computing the above test case, this isn't something I would dream of making a definitive statement about. Consider a top-heavy vehicle or a vehicle that's leaning to the side as well as uphill or downhill — that would prevent any realistic advance estimate of stopping distance.

Stopping Distance Without Brakes

At 300 mph how long would it take to stop without brakes? I'm thinking about building a 1/4 mile drag strip that can handle any speed safely so I'm trying to figure out without brakes the distance one would need to stop at 300mph.

Without brakes? You've left out some important information. If I assume a perfect car, transmission in neutral, with ideal bearings and a racetrack on the moon (or anywhere without air resistance), the car would never stop. That's never, jamais, noch nie, numquam. It would roll on forever.

You need to understand that a moving car has kinetic energy, and for the car to slow down, that energy must be converted into a different form. Wind resistance is one source of energy dissipation, brakes are another. Add imperfect bearings, tire rolling resistance and a few others.

But without knowing whether or where the car's energy of motion will be dissipated, no estimate can be given. Without any energy loss, Newton's First Law rules: "An object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force."

Thank You kindly.

You're welcome.

Sloping terrain, wet pavement, leaves on the road — Help!

I need your assistance. With a 3 1/2% downhill grade and a speed of 40 miles an hour what will the stopping distance be a 4000 pound car on an asphalt road and dry weather, In wet weather, And with wet leaves. Using the same parameters 3 1/2% downhill grade 40 miles an hour what would the similar stopping distance before an 18 wheeler Weighing 70,000 pounds. Making the assumptions that all of the brakes operates correctly all of the tires have adequate tread.

These questions cannot be answered with any reliability. There are too many independent factors. No professional would think of assigning firm numbers to a problem with this number of confounding factors. But here are some general principles:

- Point one: The mass of the vehicle should not matter, nor the number of wheels and tires, assuming the vehicle is designed correctly so the tires and brakes don't simply melt or burn under load.

To understand why, imagine five identical vehicles each weighing 7 tons (14,000 pounds) and having four tires. Test their independent stopping distances — take careful notes.

Now imagine that all five vehicles are moving close together at the same speed in a demonstration, and all of them stop at once. This will give the same stopping distance as when the vehicles stopped independently.

Now — read carefully — imagine that the five vehicles are connected together with rigid steel bars, so they move as a unit. Test their stopping distance. It will be the same as when the vehicles were not connected together, but by connecting them, you have assembled a vehicle that weighs 35 tons (70,000 pounds), has 20 tires, but that stops in the same time and distance as when they were separated.

The conclusion from this thought experiment must be that the size and mass of the vehicle doesn't matter, only that it have adequate brakes and tires.

- Point two: If you compare two vehicles with the same mass, but one has fewer or smaller tires than the other, this also doesn't matter. The reason is the vehicle with fewer tires presses those tires onto the road with greater force, and braking friction is proportional to force times area — more force, less area.

So we can assert two points: (1) vehicle size and mass doesn't matter, and (2) number of wheels/tires doesn't matter (assuming the tires don't melt under load).

As to sloping terrain, wet pavement, leaves on the road, your problem statement is not sufficient to draw a reliable conclusion. Even the dry-sloping-pavement condition is complicated by the fact that two vehicles with different centers of mass will have different stopping distances because the sloping surface places the center of mass over the tires differently, and the greater the slope, the greater the difference. So it is not possible to predict the outcome with any reliability.

A careful researcher would ask, "What kind of leaves? From what kind of tree? Does the tree exude oil in its leaves? Can one leaf ever be on top of another leaf? And how much water — damp conditions, freezing conditions, hydroplaning conditions?" That hypothetical researcher would finally say, "It is not possible to say what the stopping distance will be unless we measure it."

Vehicle stopping distance tables only work for dry, level pavement and mechanically sound vehicles, and even then there are confounding factors like temperature.

Because this looks like homework, I strongly recommend that you simply say there is not enough information for a reliable answer. If it turns out your instructor expects specific stopping distances given the stated conditions, I suggest that you change instructors.

Thank you very much.

You're most welcome.

Tractor-Trailer Braking Distance

Your explanation of stopping distance is interesting. I have a few comments though. Tractor trailers (semis) DO take longer to stop than your 5 SUV example. You are comparing apples to oranges. If you wanted to do an accurate comparison you would need to compare an SUV towing a trailer to the semi.

No, you would want to compare two SUVs in a row, but I already covered that case. But to address your example directly, imagine a tractor and a trailer, one following the other, not attached. The trailer is magically accelerated to a high speed, then its anti-lock braking system is activated. Does the fact that it has no tractor at the front adversely affect its stopping distance? No, not if the braking action is properly carried out with no chance for a jackknife.

This means that the tractor, and the trailer, cannot — indeed, must not — have any longitudinal force between them. Were this not the case, they would either break apart or jackknife. In a properly designed rig, the trailer must not ever push the tractor, because that risks a jackknife.

The reason SUVs/cars will stop quicker is because of the weight transfer to the front wheels which transfers weight to the front wheels adding to the traction of those tires.

That is true for any vehicle, with any number of wheels. It is not true — and cannot be true — for a trailer behind a tractor, for obvious safety reasons. The trailer cannot push against the tractor, that would be very dangerous.

The trailer behind the semi does not transfer any weight to the front wheels to add in braking in fact the trailer tries to continue in a straight line (Newton; a body in motion tends to stay in motion). The trailer brakes slow the momentum of the trailer but if they lock up the tendency will be for the trailer to try and pass the power unit which is able to brake better than the trailer again due to that weight transfer.

This is false and dangerous. Modern highway rigs are designed so this cannot happen, because if while navigating a curve the operator was required to apply the brakes in an emergency (or while traveling downhill, an everyday occurrence), in your imagined scenario the trailer would jackknife the tractor with catastrophic consequences.

Think about your claim. Imagine a truck braking as it descends a steep, winding road. If the trailer must rely on the tractor for part of its braking effectiveness, what happens? Remember that the trailer is much more massive than the tractor.

Modern braking systems are designed so that the tractor and trailer brake independently, with no net longitudinal force between them. All the hitch does is keep the trailer obediently behind the tractor, nothing else.

I hope this helps.

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page