Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Editorial Opinion | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

If you didn't see this coming, you haven't been paying attention.

Copyright © 2009, Paul Lutus — Message Page

(double-click any word to see its definition)

Many years ago when I was a briefly famous young computer scientist, on a TV panel show I was asked what future trends I saw. I came up with a number things — really cheap computers everywhere, a revolution in math education (no more long division, lots more higher math), the abandonment of memorization in education, things like that — obvious things. But I completely missed the significance of networking, the possibility of an Internet. I don't feel too bad about this, because everyone else missed it too. The reason we missed it was because that future development didn't leave tracks in the present.

The same thing was true of personal computers — even when people could see them in shop windows, very few realized what was going to happen (but Steve Jobs did). Indeed, when IBM built their first personal computer, they thought of it as an "entry system", a mere introduction to the larger systems that were their core business. Pretty soon we saw the tail wagging the dog.

In this article I'm going to make a prediction I'm absolutely sure of, and after reading this article my readers will lose the right to say they didn't see it coming. Unlike personal computers and the Internet, with respect to the artificial womb, the future leaves obvious tracks in the present.

Here's my prediction: Within the next thirty years, medical technologists will build a practical artificial womb. Parents will have the option to avoid the inconvenience, pain and risk of natural childbirth at a reasonable cost. This will happen.

Like every technical advance, the artificial womb will have a number of good and bad effects. This article discusses some obvious issues that will inevitably follow from this invention.

And for any Luddites who might try to forestall this development, I have to say it's already too late — there are already a number of crude ways for people to avoid childbirth and still have children. From this point onward, it's not a question of whether, but how, people will use artificial methods.

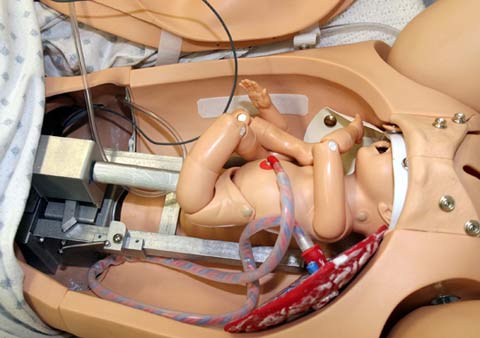

Put very simply, the core issue is the degree to which people intervene in, or accept intervention in, natural reproduction. Such interventions have a very long history — for example, the term "Caesarean section" has the name it does because, according to Pliny the Elder, the procedure was used to deliver one of Caesar's ancestors. Caesarian Sections (hereafter C-sections) have seen continuous use up to the present, gradually becoming safer.

C-sections were originally performed to rescue babies from mothers who had died during childbirth, and in those times the operation was considered fatal if the mother wasn't already dead. Over time the procedure has evolved into one that, though risky, is no longer considered a radical or extreme procedure. Recent statistics put the mortality rate for C-sections at 20 per 1,000,000 (i.e. not very risky). Although controversial, recent medical opinions estimate the risk of C-sections at three times the risk of normal delivery.

C-sections are now relatively safe and are performed in circumstances where the risks inherent in natural delivery are higher, but over time the number of C-sections performed has gradually increased. The World Health Organization has recommended an optimal C-section rate of 5% to 10% of all births. The reasoning is that both lower and higher C-section rates pose a greater risk for the mother. Notwithstanding this careful medical reasoning, at the time of writing (2009) the U.S. C-section rate is 28% of all births and continues to rise. The reasons are predictable — hospitals can charge more for a C-section than a natural birth, and doctors can avoid an accusation of malpractice that might follow a difficult or painful natural delivery.

But the present C-section controversy sidesteps a more fundamental, long-term issue, one more about anthropology than anesthesiology — the conflict between a baby's head and the birth canal. While examining the geological record of hominid species, scientists see our ancestors evolving in response to increasing brain size by way of an increase in the width of the female pelvis (Figure 1). Looking at this long-term and assuming a continuation of existing trends, it becomes apparent that people will either have to stop getting smarter or women will no longer be able to walk. But by leaving out the possibility of an artificial womb, we accept a false choice.

At this point some of my readers may be thinking, "How can we even expect to impose something so unnatural on nature?" My answer is that the entire evolution of homo sapiens has been accompanied by "unnatural" things — fire, the wheel, tools, clothing, agriculture, and what may seem the most unnatural thing of all — intelligence.

Indeed, when discussing human childbirth, intelligence is the obstacle to be accommodated and overcome. It is because of intelligence, because of brain size, that C-sections have become a reasonable option (now perhaps overused). It is because of intelligence that human infants are born so early in their development compared to other animals, many of whom can (and must) walk, then run, hours after birth (Figure 2). Compared to other animals, it's fair to say that all humans are born prematurely.

| Gestation, weeks | Survival to first birthday |

|---|---|

| 40 (normal term) | 99.94% (U.S.) |

| 26 | 85% |

| 25 | 82% |

| 24 | 67% |

| 23 | 53% |

| 22 | 10% |

But many children are born prematurely even by human standards, and until recently "preemie" survival rates were rather poor. Because of technical and medical advances, this situation has gradually improved, and at the time of writing modern methods produce the outcomes shown in Figure 3.

These recent figures represent a significant improvement over past survival rates, and it might be said that over time, medical technology is gradually allowing more gestation time outside the womb — but as an extraordinary medical intervention, by no means preferable to the natural course of events.

At the opposite end of the process, conception and embryo implantation is increasingly being aided by methods such as "In vitro fertilization" (IVF), which essentially means the first steps in conception are made in glass (from the Latin in vitro, meaning "within the glass").

The general term for all methods similar to IVF is "assisted reproductive technology" or ART. In these methods, both egg and sperm are combined outside the body and the combination is implanted in the mother or a surrogate mother (in this article I use "surrogate mother" to refer to gestational surrogacy, meaning the implantation of the client's embryo in the surrogate).

When we step back and look at long-term trends, we begin to see a pattern. It seems we're intervening more aggressively and successfully at the beginning and end of a natural process, gradually closing the gap on natural gestation. And the use of surrogate mothers closes the gap entirely, but in a very controversial and class-conscious way.

With present knowledge and methods, the center of the process (natural gestation) seems an insurmountable obstacle, but I predict that within the next thirty years we will learn how this part of the process works and we will duplicate it — or improve on it — outside the body. Then, just as with the personal computer, a laboratory curiosity will become commonplace, then a normal experience, and eventually a right.

Some readers may object that one cannot meaningfully compare childbirth to a personal computer — there are too many important differences, and people aren't computers. But my computer example is only meant to draw a parallel with a remarkable technology that no one expected to become part of our individual lives, until it did. Instead, we could compare walking and bicycling — bicycling has it all over walking, and few people think bicycles represent a monstrous intervention in the natural order. (I won't compare walking and driving — cars really do represent a monstrous intervention in the natural order.)

But whether we use the bicycle or the personal computer as an example of beneficial technological advance, all such technologies have one thing in common — no one foresaw that they would become part of everyday life, until they did. These comparisons aren't perfect because the path to the artificial womb certainly has tracks in the present — we expect a doctor's assistance during gestation and childbirth, some people employ technical methods at the beginning and end of the process, and some avoid the entire experience and hire a surrogate mother. This means the artificial womb will be an evolutionary, not a revolutionary, development.

The artificial womb won't be revolutionary, but its effect on the lives of women certainly will be.

The single most important distinction between men and women lies in their different roles in the process of childbearing. Many have argued that, without this difference, there would be very little noteworthy difference between the sexes, and much of the social structure, discrimination, traditions and myths that separate men and women would evaporate.

As women have acquired the civil rights they deserve, as they have ascended in social status, the discrimination of the past has been declared illegal, even though not eliminated entirely. But when explicit discrimination is removed as a factor, a number of perverse effects become apparent. One is that, in order to have a family, women must interrupt sometimes promising careers in order to have and raise children. This places women at a disadvantage compared to their male colleagues in the same line of work.

For those women who decide to forgo family in favor of career (let's call them "career women"), a longer-term effect takes hold, one arising from the theory of evolution. Let's say for the sake of argument that career women have genetic traits that distinguish them from stay-at-home mothers and housewives. If this is true, then because career women (as we've defined them) don't have children, their traits are selected against in the evolution of the species. This could become a powerful force against any overall change in the status of women, selectively removing an appreciation or aptitude for careers over a long period of time.

Educated readers may argue that small variations in genetic endowment aren't efficiently transmitted to children by individual parents (an idea called "Regression toward the mean"), and this argues against the idea that a career woman's children would turn out significantly different than those of a housewife. This is true, but as it turns out, what is true for individuals isn't necessarily true for populations, and a tiny, statistically insignificant effect in particular individuals can over time become an overwhelming effect in the population to which that individual belongs.

This large-population statistical effect is particularly important if the genetic difference between two groups confers a survival advantage, in which case a seemingly trivial difference in genetic endowment may in time become a trait shared by all members of a species.

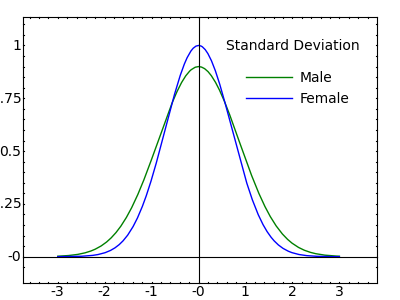

What this means for gender issues is that any choices individual women make that prevents them from having children (or as many children) will over time be selected against by evolution, an idea I call the "Population Paradox". This same logic doesn't work for men, who might spend 30 seconds starting a process that may require years of a woman's life. A consequence of this idea is that men can show a wider spectrum of traits while remaining reproductively fit, but women have fewer options that allow them to reproduce and contribute to the gene pool. If this idea is true, women will show a narrower spectrum of behaviors and traits (those that allow them to bear children) than men, even though men and women are equal overall.

This is a relatively new idea that is creating much controversy and discussion, so I would like to spend a few minutes on it. If a man spends years working in a corporate boardroom, or out in space exploring other planets, or being a criminal, or in devotion to mathematics or science, and if these choices would in principle prevent him from taking a nine-month break two or three times during his most productive (or destructive) years, this won't keep him from contributing his genes to the next generation, but it would keep a woman with the same talents from doing the same thing.

The overall effect of this idea on the human population is shown in Figure 4, where men show a wider mixture of traits (both better and worse) than women, with the outcome that men and women, although equal in intelligence, exhibit a different spread of behaviors. I emphasize the trait-spread theory is actually just a hypothesis with no supporting evidence (in science, the word "theory" is normally reserved for ideas that have some supporting evidence).

One can judge how controversial this theory is by noting that Lawrence Summers, former President of Harvard University, was forced out of his position for bringing it up during a public address. But public controversy doesn't constitute scientific evidence for or against an idea, and some of the alternatives to the trait-spread theory are even more controversial and questionable (e.g that women are congenitally unsuited to technical and scientific work). It's important to emphasize that none these ideas is supported by evidence, and no reliable distinction can be drawn between men and women in aptitude and I.Q. tests.

The basic meaning of the trait-spread theory is that, because men can engage in more behaviors while remaining reproductively viable than women can, over time this may produce an overall difference in the standard deviation (SD) value (the width of a population's distribution) of standard measures like I.Q., with men showing a larger SD than women, even though the population mean is the same for both groups. It's well-established that men and women don't differ in I.Q. measurements, and it's also well-established that there are fewer women at the highest levels in science and technical fields — and there are fewer female criminals and sociopaths.

Although the male and female curves in Figure 4 look much alike, if one looks closely at the region around SD 2.5, corresponding to an I.Q. of 137.5 (very bright), one might see a male-female ratio of 3:1, and the same ratio at an SD of -2.5, corresponding to an I.Q. of 62.5. This distribution would mean more bright, and more dumb, men than women, and agreement with the observation that male and female I.Q. scores tend to be equal.

It is essential to say again that the trait-spread theory is formally a hypothesis with no supporting evidence, the graph in Figure 4 is just an illustration with no basis in data, and the controversy about women in science may be more simply explained another way. It is equally important to say that, if this theory is borne out in future studies, the artificial womb will have the effect of reducing or eliminating the source of the difference — the fact that women have a larger investment in childbearing than men, and are therefore either (1) obliged to forgo having children, or (2) are unable to focus on their careers to the degree that men are.

The trait spread theory, or something like it, is the basis for saying that the artificial womb will have a revolutionary effect on the lives of women — it will erase the traditional commitment disparity between the sexes with regard to reproduction, this in turn will allow more women to pursue more kinds of careers and activities, and this will reduce or eliminate the theoretical disparity shown in Figure 4.

At present, women who want to pursue careers but who also want families have a number of nontraditional options, including hiring a surrogate mother to bear her children. At the moment this option is limited to wealthy individuals, and the class distinction between surrogate mothers and their clients should be clear. Indeed, because the surrogate mother spends valuable reproductive months bearing someone else's child, this represents a reversal of the evolutionary bias against career women described above (the surrogate-mother option favors the originator's genes over those of the host). The only reason this isn't an important statistical effect is because of the small number of surrogate mothers at this time.

In the future this might change. Since the mid-twentieth century there has been a widening of the gap between rich and poor, accompanied by an erosion of the middle class in many parts of the world. This may produce a market for surrogate motherhood unimaginable at present. Until the artificial womb appears, we might see development of an exploitative market in which the poor bear the children of the rich.

Readers might realize that, before the artificial womb, there might be such an exploitative market, but on the first appearance of the artificial womb, rich women will be able to afford the technology but poor women won't. So what's the difference? The difference is the same as that between a human-powered rickshaw and the first appearance of a bicycle — the rickshaw represents a clear and visible exploitation of a poor person by a rich one, while the bicycle represents technology that might eventually become cheap and commonplace through market forces and mass production.

This doesn't argue that pedaling one's own bicycle is always less exploitative than hiring a rickshaw, but the bicycle has more long-term social leveling potential than the rickshaw does. In the same way, the artificial womb will certainly start out as a rich person's option, but may become commonplace by a gradual process of technical advance, after which it may prevent the exploitation inherent in surrogate motherhood, as well as erase the only significant distinction between men and women.

I don't think most people even try to imagine what the world would be like if we could somehow eliminate the single most important difference between men and women. But I have to say that, when I hear someone romanticize the present differences between men and women, in particular if they describe women as particularly vulnerable and in need of special treatment, I want to throw up. I've always felt that way, and I think many women share the feeling.

When I was young, I took some views on gender issues that I now recognize as unrealistic and naïve. For example, I decided that prostitution represents the systematic exploitation of women, so, being young and idealistic, I resolved never to engage the services of prostitutes. When I made this decision, I was too young to realize it eliminated the possibility of marriage to anyone but an equal, and studies show most marriages aren't between equals. Since then I have had any number of relationships that ended when the woman demanded payment for simply being there. (These are not statements about women, they are only statements about women I have known personally.)

Over time the women I met and knew personally became more ingenious at getting money from me. Some simply stole it, others used what is now called "social engineering". One woman announced she was having medical problems and, because it was a medical emergency, she needed me to pay her medical expenses with a local specialist, so I agreed. After several weeks of identical financial requests I realized she showed no signs of getting better, so I asked to meet the doctor. It turned out this woman had invented the doctor and had opened a bank account in her name, all in order to get money from me.

The philosophical basis for these personal experiences was my early resolve to treat women as people, not in any special way based on their gender. I will say this well-intentioned resolve has been a complete disaster, and I have had endless relationships that began in a normal way, but once they became sexual the demands for either money or marriage started — always, with no exceptions — and killed the relationship. My favorite quote from that time, from a college-educated woman, was "Men give women money — that's what they're for!" I'm in my 60s and I've had any number of relationships over the decades, most of them embarrassingly short. Every one of them fell apart once the woman realized I expected partnership, not a hired sex object or a paid housekeeper.

It seems my naiveté is boundless. After watching the above-described pattern establish itself, I believed things would improve as time passed — I hoped that the women I met would mellow and begin to want some of the same things I wanted. But if anything this represented naiveté squared — over the years the women I met progressively offered less while demanding more, to the degree that I've given up and am quite satisfied to be single.

None of this is meant to suggest that there are no extraordinary women — there certainly are, and they achieve plenty in every imaginable field of endeavor. To me this means any woman can achieve anything she chooses to accomplish, but that there are many women who, for one reason or another, are not making the choice (or who choose to have a family instead).

I will never accept the idea that there are any important differences between the sexes that arise from anything but personal choice and the burden of childbearing. And the artificial womb will eliminate the second of these factors.

I want to end on a positive note. During my time spent designing part of the NASA Space Shuttle many years ago, I befriended a very appealing, intelligent woman in a similar professional position on the project. One afternoon she asked me to consult with her on a Calculus problem. Working together through the afternoon, we came up with a compact mathematical description of a solid whose exact shape and volume needed to be computed efficiently. I happen to be able to solve this kind of problem, and she was equally skilled in this mathematical specialty. It was a creative task and great fun.

At the end of the session I told her exactly what I thought. I let her know how much I admired her, and how the kind of creative work we had just done together was my idea of heaven. I told her I understood that she was in a perfectly acceptable relationship and that there was no reason to think I would represent an improvement over what she had already, and I was glad we could share professional experiences like that work session. I thanked her for a perfect afternoon and we parted ways.

I wrote this piece because I think an artificial womb is an obvious, foreseeable result of existing technical trends and because it will produce a big change in relations between the sexes (like The Pill but on a larger scale), but also because I'd like to see a world where the only reason women don't win half the Nobel Prizes is because of choice — not the preferences of men, governments or religions, not an overwhelming force of nature and biology, but their own choices.

This issue is moving forward faster than I expected:

| Home | | Editorial Opinion | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |